Monograph reviewed for French History, Volume 32, Issue 4, December 2018, pp. 615–617. doi:10.1093/fh/cry078

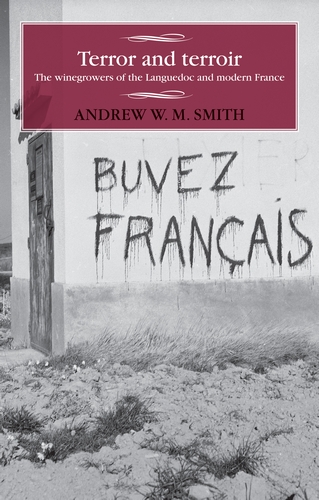

Summary: In the summer of 1907, France’s Midi rouge (the ‘red South’) was in revolt, with regular Sunday protests in towns throughout the region drawing as many as 600,000 participants. After protesters torched buildings in Narbonne, the military occupied the town, leading to the deaths of six people and the mutiny of a locally recruited regiment. The cause of all this upheaval? A dramatic downturn in the price of wine, specifically the vins de table on which the regional economy of the Languedoc depended. Local leaders, allied with the Socialists, demanded government intervention to protect small-holding winegrowers from fraud (by larger producers allegedly adding sugar to their wines) and from competition with foreign labour. According to Andrew W. M. Smith’s Terror and Terroir, this militant, direct action by regional winegrowers in the early twentieth century created a foundational myth and set a pattern for subsequent protests in the post-war period, as the region faced new challenges from the modernization of agriculture.