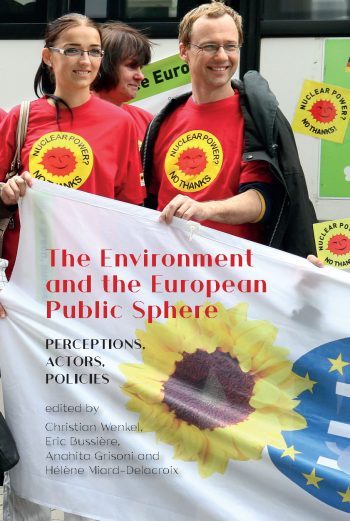

Chapter published in Christian Wenkel, Eric Bussière, Anahita Grisoni and Hélène Miard-Delacroix, eds., The Environment and the European Public Sphere: Perceptions, Actors, Policies (Cambridge: White Horse Press, 2020), 124–146.

See a review of this book here.

Abstract: During the 1970s, opposition to nuclear energy was structured primarily by local siting decisions related to national nuclear policies. However, the anti-nuclear movement sometimes defined itself as ‘international’ or ‘European’ in view of the transnational links that existed among activists – as well as among their opponents in state and industry. This chapter examines three visions of ‘Europe’ articulated by the movement: first, the ‘Dreyeckland’ imagined by French, German, and Swiss activists near Wyhl; second, NERSA, the European consortium behind the construction of the ‘Fast Breeder’ plant in Malville; and, finally, the ‘Europe of peoples’ called for in Gorleben, where the ‘Free Republic of Wendland’ was realized along the border with East Germany in May-June 1980. In focusing on these examples, I show several ‘Europes’ of the 1970s: utopian and dystopian, real and potential, of varied spatiality and geometry.

Les activités du mouvement d’opposition à l’énergie nucléaire des années 1970 étaient en premier lieu structurées par les implantations locales de centrales nucléaires qui s’inscrivaient dans des politiques nationales d’énergie. Cependant, ce mouvement se définissait parfois en tant qu’« international » et/ou « européen » en vue des liens transnationaux entre militants – et entre forces pro-nucléaires. Ce chapitre s’occupe de trois visions d’« Europe » articulées par ce mouvement : d’abord le « Dreyeckland » imaginé par les militants français, allemands et suisses près du site de Wyhl ; puis la NERSA, consortium européen constructeur du site de Malville ; et enfin « l’Europe des peuples » à laquelle on faisait appel à Gorleben, lieu de réalisation d’une « République libre de Wendland » en mai-juin 1980 à la frontière avec l’Allemagne de l’Est. En se penchant sur ces trois exemples, je montre plusieurs « Europes » des années 1970 : utopiques et dystopiques, potentielles et réelles, à géométries et spatialités variables.